Friendship and games from Shutterstock

Filed under: Articles, Collaboration and social, Digital workplace, Intranets

Compelling, creative, addictive and a key tool in improving employee engagement. This isn’t the way most intranet managers would describe their sites. But that could all be about to change.

The use of game theory and gaming mechanics in business application development is intensifying day by day, and there are already a number of examples where lightweight gaming mechanics are being integrated with intranets and related information systems.

In this article I’ll look at how gaming mechanics are in use in business, how this innovative stream of application design could be coming to your business soon and why, together with other principles, it might help fulfil a vision for the future of intranets.

Game theory?

What exactly is game theory? Millions of words have been written about it, and even a brief introduction can take up a volume. However, calling on Wikipedia (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Game_theory) for a summary:

“Game theory is a branch of applied mathematics that is used in the social sciences, most notably in economics, as well as in biology (most notably evolutionary biology and ecology), engineering, political science, international relations, computer science, and philosophy. Game theory attempts to mathematically capture behaviour in strategic situations, in which an individual’s success in making choices depends on the choices of others.”

Gaming mechanics are being integrated with IT systems

If you’ve come across the term ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’ before, you’ve come across game theory.

If you watched the 2009 film, ‘The Dark Knight’, and squirmed as the late Heath Ledger’s ‘Joker’ character pitted a ferry of prison inmates against a ferry of Gotham City citizens, and tried to entice each of them to blow the other up with a bomb, you’ve seen the Prisoner’s Dilemma played out.

In fact, the more one learns about game theory, the more it can be seen everywhere.

Gaming mechanics

Gaming mechanics are the rules, tools and landscapes of game theory. The boundaries in which you play a game and the actions by which you progress through it, define strategies and approaches to how you play the game: if you complete ‘x task’, you get ‘y reward’. If you complete a number of tasks, you get ‘z reward’. If you fail to complete any tasks you get nothing. There are the tools to help complete the tasks. The more tasks completed, the better the tools get.

What’s this got to do with intranets?

Until recently, game theory’s visibility and application in software-based, frontline staff engagement tools was limited. Companies struggle to effectively determine what ’employee engagement’ is, let alone apply something as seemingly unrelated as game theory and mechanics to the software that employees use.

But gaming mechanics can also fall under the much better understood business terms of ‘reward and recognition’, incentives, bonuses and so on — something every company is keenly aware of. It’s the incentive aspect, the motivation to do more than is normal, to go the extra mile to achieve, that ties game theory and mechanics directly with intranets and employee engagement.

Virtual environments

The bigger picture of gaming mechanics and business software begins with virtual environments. Second Life and other ‘metaverses’ have been touted for some time as areas for business expansion, offering employees new ways of interacting and drawing on ‘avatars’ (virtual representations of people), and increasingly powerful, immersive graphics. So far, though, metaverses have failed to gain mainstream adoption. The emphasis on mainstream doesn’t mean the field is dead, however.

David Holloway is editor of the Metaverse Journal (www.metaversejournal.com) and a virtual worlds consultant. Aside from managing one of the most popular specialist virtual world websites, Holloway also advises in a number of industries, most recently working with the Australian film industry on the movie ‘Beautiful Kate’, which featured a virtual world-based scene.

Virtual worlds have failed to gain mainstream adoption

Virtual lives

Holloway says that, away from the headlines, progress in the field of virtual worlds has been non-stop.

“For enterprises, virtual worlds have been great since 2007, and there’s certainly been an increase of virtual worlds for remote meetings, training and similar events. The global financial crisis increased interest for that, and some VW companies touted their products on that basis.”

“Perhaps the biggest thing that’s happened recently is Linden Lab, the creators of Second Life, released an enterprise version of the software (work.secondlife.com/en-US/) that can be deployed on an organisation’s own servers.”

On its site, Linden Lab says Second Life is “perfect for virtual working and collaboration”. It touts case studies from the likes of defence and security firm, Northrop Grumman, and computer chip giant, Intel, which have used the system for what can only be described as cutting-edge virtual collaboration — these are two companies at the very forefront of technology, after all.

“Linden Lab also open-sourced the original code for Second Life, calling it OpenSim, which is also seeing rapid uptake”, continues Holloway. “And these systems have come a long way from 2006-07 when Second Life was in the news a lot, but those who tried it were scared off by the steep learning curve and clunky user experience.”

In this respect, collaboration and teamwork is easily associated with gaming theory. There’s an emphasis on working together virtually, in a video game-style environment.

But while collaboration and teamwork in virtual worlds is a growing area of development, such environments seem to require too much of a leap for most businesses. The technical requirements are still too heavy, the learning curve still too steep, the concept seemingly still too inane for all but the most progressive organisations.

Away from immersive virtual environments, it’s the smaller, individual mechanics of game environments that are beginning to gain mainstream adoption.

Multiplayer gaming on the internet

On the web and in video gaming generally, massive multiplayer online games (MMOGs) include dedicated PC and console titles such as World of Warcraft, The Sims, and Call of Duty. On sites like Facebook there are also lighter games such as Cafe World, Farmville, the newly released Frontierville, and Mafia Wars. Such games are seeing millions of hours of play, and they’re creating tens of millions of workers, current and future, who are completely at home in competitive, online environments.

‘Competitive’ is a vital word here. In these games, the mechanics of acquiring reward points, trophies, badges and prizes, and the lure of ‘levelling up’ to unlock further rewards, keeps players coming back and competing with each other, sometimes for days on end. ‘Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2’ has 700 multiplayer levels, which tens of thousands of players have completed. The game itself is R-rated, and has over 20 million players. As of June 2010, Farmville had over 82 million active users. Mob Wars also has over 25 million active users.

Yet, and some might say surprisingly, these players also invariably help each other. They create teams and ‘clans’ on the fly, share tips and discuss tactics via related forums and web-based communication channels, from email to in-game voice and video calls. This is a behaviour called, ‘co-opetition’, defined as ‘Where people with collective interests can assist each other with some things, while still remaining fiercely competitive in other areas’. Co-opetition is a fundamental by-product of network-based gaming.

It’s these underlying gaming mechanics, and in many instances the co-opetition behaviours, that are providing businesses with fresh ideas for motivation and rewards programs in business environments.

“The social gaming sphere is big”, says Holloway. “For businesses, gaming mechanics can help to substantially increase engagement by providing virtual goods, prizes and so on, for employees who perform well in their roles. There’s a huge amount of interest in this.”

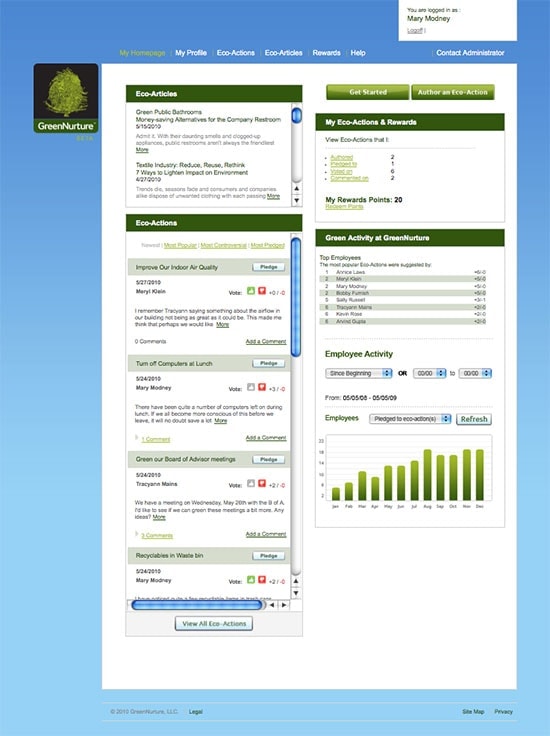

Figure 1. GreenNurture is a web-based social media application featuring gaming mechanics. Employees suggest sustainable initiatives and colleagues can ‘pledge’ to support them.

GreenNurture allows employees to ‘pledge’ support

Gaming to be green

At the 2010 IBF24 event, a 24-hour online intranet conference held at the beginning of June and produced by the UK’s Intranet Benchmarking Forum, CEO Derrick Mains demonstrated his company’s web-based, sustainability-oriented application, GreenNurture (Figure 1).

Designed to provide motivational ties to suggestions on environment and sustainability issues, GreenNurture was launched in March 2010. It enables employees to suggest environmentally friendly improvements for a business. “It’s a suggestion box on steroids”, says Mains in his GreenNurture demo.

With GreenNurture, fellow colleagues can ‘pledge’ to support co-worker initiatives, and pledge points are gained and can be redeemed via Recycle Bank, for products and services from 2,500 brands and retailers in the US and UK. To assist with devising the pledge system and mechanics, GreenNurture employed the services of one of the top game theory specialists.

Key to the system is the focus on sustainability, and not day-to-day roles. It’s acutely focused on additional actions that encourage employees to go the extra mile in and for their organisation, and it rewards them for doing so. The GreenNurture application then supplements their activities with further information, statistics and social networking capabilities to create the business-equivalent of a competitive gaming network, but focused on sustainability. The Wall Street Journal recently called GreenNurture “One of the best ways for a small business to become eco-friendly”.

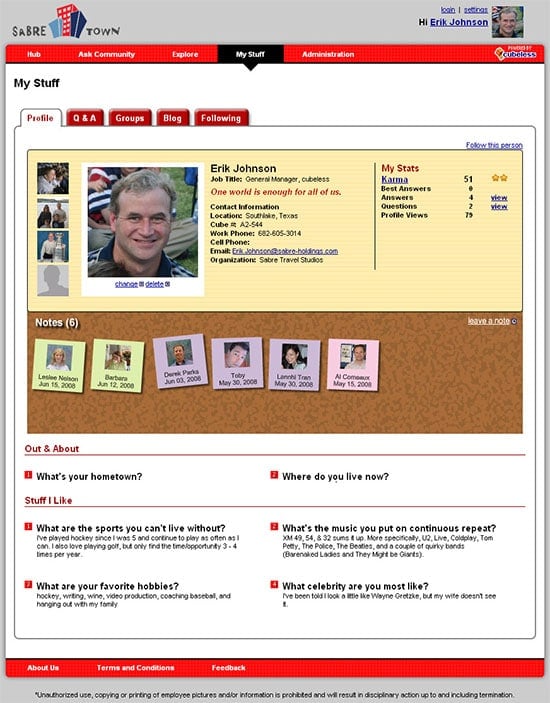

Figure 2. Sabre Town features a ‘karma points’ system, which was designed to set behaviours and motivate employees to particip[ate in and contribute to the new Sabre social network

Gaming to be good

‘Sabre Town’, the wildly successful, award-winning social networking platform produced by Sabre Travel Studios, features a ‘karma points’ system. This was devised in-house by Sabre Town Manager, Erik Johnson, and his team.

“The karma system was originally developed to set behaviours and motivate people to contribute to the Sabre Town network”, says Johnson. “Each time an employee answers another’s question on the Q&A board, karma points are awarded to the individual for ‘doing a good thing’. The user gets more points if their answer has been marked by others as ‘helpful’ and further points if the answer is marked as ‘best answer’.”

“Increasing karma scores unlocks the ability to post more pictures and belong to more groups in Sabre Town. It becomes a bragging right within the organisation”, says Johnson. “But bragging doesn’t go on forever. A person new to Sabre Town will take around two to three months to achieve all the targets there are to achieve, however the number of points are not limited.”

The karma points system has been highly successful at Sabre and at other organisations now using the same underlying platform, Cubeless. Because of karma points and other mechanisms, Sabre’s Q&A board has an 88% response rate in 24 hours and a 97% answer rate overall. In the last 30 days, over 50% of the organisation have logged into Sabre Town. These are remarkable participation statistics for such a platform.

At another organisation using the Cubeless platform, the karma points system became so competitive that the organisation had to hide the scores from other users. Individuals could see their own scores, but not their colleagues’ scores.

“We’ve been surprised at the success of this particular feature, it can take on a life of its own”, adds Johnson. “It really brings an active, interesting aspect to the platform.”

‘Bragging rights’ is something Mains also talks about with GreenNurture. An employee’s suggestions and proficiencies are on display for the rest of the organisation. “It becomes a bragbook”, he says.

It’s not all fun and games

There are some less enthralling aspects of gaming mechanics in this context. Bragging isn’t always a desirable behaviour in the workplace, for example. For some employees, watching colleagues brag about their success is frustrating, not motivating.

Other critics jump on the idea of giving ‘even more reward’ to employees who are already rewarded for doing their jobs. Talking with one senior manager at a large FMCG, the response to the concepts outlined above was clear: “Why should we offer even more incentives? People already have work, and bonuses for hitting targets. They shouldn’t need motivation beyond that. The more we give, the more they expect and the lazier they seem to get.”

Further counter points include the suggestion that people will find it childish. There’s also the issue of the quality of exchanges, or even online bullying or harassment in the workplace. Anyone that’s played online games will tell you the conversation and exchanges aren’t usually of a particularly savoury kind. Foul-mouthed players, obscene insults and bullying are genuine concerns for businesses and games networks alike.

And what about time? Would employees spend more time ‘playing games’ than doing their actual work?

Then there’s the time-old tradition of ‘gaming the gaming system’, i.e. cheating. Boosting rewards, artificially or by other methods, falsely reporting targets and examples of misdemeanours are easy to recall, whether discussing video games — or credit default swaps. How can these business games platforms be fair?

Erik Johnson says Sabre Town’s points-awarding algorithm prevents people gaming the system. “It’ll award a user once for a task, they can’t then go back and complete something over and over again. And, there’s a limit to what can be awarded. As said, it’s not open-ended. Aside from gaining more points, after a while the tangible rewards and unlockable features are exhausted.”

While legitimate, the concerns aren’t black and white. We’ve also seen some of these arguments played out before elsewhere, including recently with social media.

Old arguments

Social media on the web features millions, if not billions, of anonymous comments and faceless exchanges. On the web there’s little accountability for comments. Blog commenters frequently hide behind anonymous names or pseudonyms.

In a business, however, it’s widely accepted that participants in online social exchanges are accountable. Their names are attached. If an employee tries to cheat the system, they’re accountable. If they’re foul to a colleague, they’re accountable. If they’re wasting time and not getting the job done, then that’s a managerial issue and can happen whether there’s games, social media, or even a newspaper involved. The tool of behavioural misdemeanours isn’t the core issue.

“Some people have also complained that it’s silly and goofy”, says Johnson, “but for the most part people have really enjoyed the karma system”.

Time to get gaming?

With all of those considerations and the technical aspects of implementing game-based systems on, or as part of, an intranet, a practitioner might be forgiven for saying, “Not here, not now, no way”.

But intranets are entering exciting times. Going beyond static content management, and even the buzz around social media and two-way dialogue, the future is all about active, dynamic, compelling systems that empower employees to work in equally dynamic and compelling ways.

Gaming mechanics point towards an intelligent future for intranets, where proactive systems, designed with people at the centre, form an organisation’s central intelligence and task completion point. It’s a future where employees like to use the systems they have. They want to contribute to the business, they are engaged with it. Game mechanics are not a panacea to engagement or a dead intranet, but they’re one potential component in a system that’s useful, valuable and ultimately desirable to employees and the organisation.