Writing a diary from Shutterstock

Filed under: Articles, Intranets, Usability

Often it’s difficult to tell exactly who is using an intranet, and how they are using it. Obviously, some research is required to help answer these questions, but what technique can capture the tacit knowledge without shadowing users in an uncomfortable and expensive way?

A relatively recent research technique that can be very useful in this situation is known as a ‘cultural probe’. In essence, the technique involves getting users to give you information without you actually being there. Often this means giving them a diary to write things down in, but the technique can make use of all manner of objects.

The name of the technique usually raises some eyebrows, but it is also known by other names, such as: ‘diary study’, ‘cognitive probe’, ‘reality research’ and ‘multimedia study’.

In a departure from the typical KM column format, this article follows an interview with well-known proponent of probes, Gerry Gaffney, founder of Melbourne-based user experience consultancy Information and Design.

Step Two Designs recently talked with Gerry about his experience in using cultural probes, in particular for intranet design research.

Figure 1 – A typical probe includes a diary which users fill in.

S2D: What are cultural probes?

GG: First of all, I don’t like the term probes. It’s not a very client friendly term. To me, it’s a bit like saying ‘heuristic evaluation’ — while practitioners might have some idea what we mean by those terms, and even that in my experience is not a given — clients certainly don’t know what we mean by it.

Having said that, ‘cultural probe’ is actually a very good description of what these things are about. If you think about a probe as something you send off into the unknown — typically I use the analogy of a space probe like Voyager — it’s something that goes somewhere where we can’t go ourselves and transmits back data. So ‘probe’ is a very appropriate word.

And ‘cultural’ is a very appropriate word too, because it is looking at culture in terms of the way people act, behave and what their beliefs are.

But while it’s a very accurate name, it’s still rather obscuring. I would typically use the term ‘diary study’ when talking to a client because people will know what you mean, which is you give people a diary and ask them to fill it in every day, or whatever.

That’s essentially what a cultural probe is about, you give people the materials to enable them to self-report and send information back to you.

Give them materials to self-report and send back to you

S2D: How have you used probes for an intranet project?

GG: I’ve only used them on one intranet project, and that was for a major retailer here in Australia. To be quite honest I hadn’t actually thought of using probes in this particular project, it was a colleague of mine who suggested we could combine the activity we were already doing, which was a ‘contextual enquiry’, with a diary study.

We gave the users we had visited some diaries on conclusion of our contextual enquiry and asked them to complete them and send them in. We gained some additional information which largely confirmed what we had found out during the contextual enquiry. The key activity was very much the contextual enquiry — the diary study was an adjunct to it.

S2D: How did the client respond to the idea?

GG: They were very open to it, and in fact the person who suggested it had worked for the client for a fairly long period, so it was coming from a trusted person within the organisation.

It was also an extremely low cost adjunct to what we were doing, so we didn’t have to go through any approval process. There was no suggestion at any stage that we shouldn’t do this.

Generally, cultural probes are a very good way of finding out about people, and I think clients are very open to it, if it’s what they need to do. For example, another one of my clients, LinkMe, wanted to know more about their users.

They had been conducting interviews and meetings with users and so on, and a cultural probe was an excellent way to look at an activity that doesn’t happen at one point (like job hunting or job seeking) and exploring the sorts of things that people go through, and we got a very rich set of data out of that and it lead very strongly to a set of personas and scenarios. Of course, one of the key things with personas is making sure they are based on actual data, and cultural probes are a great way of getting that data.

Cultural probes are a very good way of finding out about people

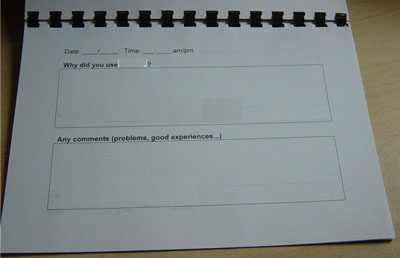

Figure 2 – The diary used for the retailer intranet project.

S2D: What exactly was the probe in the case of the retail organisation?

GG: It was a little A5 diary that was quite free-form. We put it next to some computers where we wanted to monitor intranet usage and we just said if you use the intranet, please take a minute to tell us about it.

All it had was a space for a date and time, ‘what you did’ and ‘any comments’. There were no guiding questions. This is an interesting point actually; in other projects we’ve looked at guiding questions but concluded that if we’re trying to find out what’s really going on there, we don’t want to lead them.

The originator of cultural probes, Bill Gaver, takes the very academic view that you just send this stuff out as open as possible, and in fact he doesn’t even do any formal data analysis of what comes back. He says, what you get from the cultural probe is what you get from the cultural probe, and that’s your data. Whereas I feel that in a commercial context, you want to be producing a deliverable out of it. And in this case we developed personas and scenarios.

S2D: What as the process you used?

GG: The typical process of one of these studies is that you choose your participants — the same as you would for any other research activity — you brief them on what you want them to do, and then give them materials in order to achieve that.

Typically you have at least one follow-up interview during the course of the probe activity to make sure that you’re getting the type of data that you want. And then you have a debriefing, typically individual sessions, although that’s not mandatory. You go over the materials that people have collected and get further data from that interview.

You can then take the data you’ve gathered and use it towards producing things like scenarios and personas, and in fact I’ve found that cultural probes are particularly good for generating both of those things.

S2D: What preparation was required?

GG: For this particular retail project, a tiny amount of time, maybe one person-day all up. Firstly it was straightforward and secondly it was an adjunct to a contextual enquiry activity, so we just ran the diaries off on the laser printer, bound them, and at the end of the site visit we’d say “do you mind filling this in?” and there’s an address on the back to send it back to us, and it came back in the internal mail.

S2D: Who participated in the study?

GG: Overall, the project was focused on employees in the stores, as opposed to those in head office. The intranet is not aimed at everyone throughout the organisation, so we were looking at people in the stores who were users of the intranet.

The people doing the diary study were the people involved in the contextual enquiry, but it was also people peripheral to them. So let’s say we were interviewing an individual for the contextual enquiry, we gave them the diary and asked them to tell anyone who uses the intranet on this machine about the diary — and in many cases they were shared machines.

And that’s largely an artefact of the environment we were in; a lot of people were using a PC that’s in an admin/office area, rather than having their own PC. If you go into your local store, you’re not going to see each department having their own computer online. It’s typically only one in a shared area somewhere.

It was quite notable that when we got back some of these diaries, we’d have three or four different handwritings because three or four different people were filling it in.

We did also back up this type of research with some interviews with head office staff who dealt with the stores people as well, and with helpdesk and so on. So it was part of an overall research activity.

S2D: How long did you leave the diaries out there?

GG: For this project, we left them out for about two weeks. It was fairly open, we had a date on the diary but said please return it around such and such a date. And because it wasn’t the central activity we were doing, it was less time critical.

S2D: How many people participated?

GG: We had about 15 people all up that we did site visits with, from about eight stores, but given that some of the diaries were filled in by more than one person, we were probably getting coverage from more than 20 people.

S2D: How did the participants react?

GG: On the one hand it was something they hadn’t done before, but on the other hand it was a really trivial activity, we weren’t asking them to do something that took a lot of thought.

And it was completely optional, it wasn’t mandated by their managers or the company or anything. So all they had to do when using the intranet was flip open this diary, scrawl in “I looked at this”, put the time and date, then “I looked for that and no problems” or “I looked for this and it didn’t load up” or “the system was too slow” or whatever it happened to be. So there was very little onus on them to do anything.

A few of the diaries came back blank, and this is fairly typical in my experience with cultural probes; you’ll get some people who are avid diarists and are totally into the whole thing and report huge amounts of information, and others who report back small amounts of information.

On this particular project, we didn’t have any means to follow up the people who produced little or no information, nor did we have any intent to. But in other projects that I’ve worked on, the people who were reluctant to diarise, or who were not necessarily prolific, are often the most useful — they’re worth pursuing.

People who are reluctant to diarise are often the most useful

S2D: How did you analyse the data?

GG: Bill Gaver’s approach is that you get back what you get back, and you sort of mull that over, and that is the data set. And that seems to work exceedingly well for him.

However, I think that most clients would expect to see deliverables at the end of the day. How would it look if I said to client I want to go and spend a reasonable amount of money for a user-research activity and at the end of it we don’t know what we’re going to have?

In the case of the retail organisation, by the time we got the diaries back we had already completed a lot of analysis of the data from the site visits. The people who did the site visits had made extensive notes while they were out there, they had taken photos, made notes of artefacts that were in use and so on. We had taken all that data and printed it out on index cards and done a very big affinity diagramming exercise with it and written up a report.

The report was approaching final draft as the diaries came back so we transcribed all the issues that were in the diaries — which is not a huge job, maybe a couple of hours’ work — and added them as appendix to the report. And in a few places went back and tweaked the report.

There were no surprises in the diaries, because we had found out in the contextual enquiry all the things that were in the diaries. There was however validation, so that where we had collected comments regarding lack of access to computers, for example, the diaries very much validated the stuff we already had.

So in the grand scheme of things, they had a fairly minor impact on the report, but we could go back and say this has been validated, this really is an issue in the field, we’re seeing it.

The diaries validated the stuff we already had

S2D: How many people were on the project team?

GG: There was a core team of two people involved in the work. Other people came in from time to time — such as when we did the affinity diagramming an additional person (from the intranet team) was involved — but basically it was a core team of two people who did the bulk of the work.

I’d like to see two people involved in anything like this; when doing this on your own you don’t have anyone to bounce ideas off, so I think two people is good both from a logistical point of view and from the quality of the data analysis.

S2D: What strange things do you get back in probes?

GG: I worked on one particular project where we were looking at people in the home environment, and there was one chap who was really odd. When we had the initial briefing session he turned up about an hour late, he was really, really disorganised and he failed to fill in the diary, he failed to take any photos and so on.

And his home environment was really quite odd, so it was tempting to write him off as an outlier. But the more we looked at him he turned out to be quite an interesting person because a lot of the attitudes he had were, while somewhat extreme, very definitely on the continuum of the factors that would affect how people were going to interact with this particular product. So he was very useful, but that was kind of weird.

Generally speaking, it’s like anything, you get a range of people and personalities, and some of them you think “gee that was a bit odd”, but that’s just the way humans are, I guess.

For the retail organisation intranet project, there wasn’t anything like that. You could see levels of frustration at certain aspects but a lot of people we visited had no problem, they’d just say “Yeah, it does this, and it’s fine” — routine day-to-day types of things.

But there were a couple of people who were frustrated and you could see the same person harping on about the same thing, entry after entry, as if to drive home the point they were trying to make.

Another thing that stands out from the information we got back was one of the people from a store, right at the end of the diary, wrote a little thank you note, saying they really appreciated the opportunity to have their say.

Actually, that’s not all that uncommon. When we’ve done probes for other things people have often become very reflective as a product of doing the study. It didn’t really happen with the retailer job because it was a very narrow focus, it was really just about usage of the intranet, but in other places where we’ve looked at a wider range of things like job hunting for example, sometimes people become quite self-reflective. We’ve had people say “I wish I’d started this diary thing before” or “I wish I’d kept my own diary of this particular activity”. It gets people to reflect.

S2D: Do you have any advice for someone thinking of using probes?

GG: You need to be really careful about the people you’re recruiting, because typically you’re asking them to put in a fair amount of effort (compared to a survey or interview) and if you’ve got the wrong people, it’s not like usability testing where you can replace that person with another person quite readily.

Similarly with contextual enquiry, if you choose the wrong person you can often adjust your visit to see another person instead, or add another couple of people in. But you can’t readily do that with cultural probes.

If there’s one lesson I’ve learnt from cultural probes, it’s that it’s really important to do a very good briefing session. And no matter how good that briefing session is, you need to do a follow-up session fairly soon with the individuals, because some of them will have drifted off track or have forgotten about it or are not interested or whatever it happens to be. So doing a follow up is really important.

And putting a significant effort into the debrief is also very important, keeping in mind that the debrief will probably get you a lot of data that’s not in the diaries. We’ve found that the debrief session itself is a key component of the information you’re getting back from the cultural probe.

The debrief will probably get a lot that’s not in the diaries

Of course one thing about cultural probes is that you could consider doing it on a large scale, using postcards or whatever, opening it up to hundreds of thousands of people is conceivable.

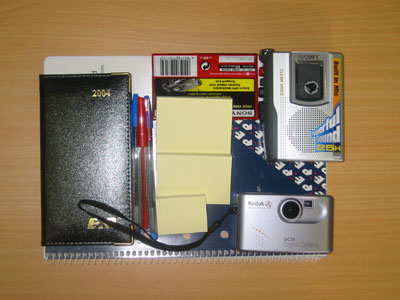

Also, I have to mention that you can use lots of different items as part of a cultural probe. I’ve just talked about diaries, but people are often given digital cameras, scrapbooks, post-it notes, stickers and all sorts of ‘idea generators’ such as voice recorders. There are many different things you can have as part of these cultural probe packs.

When working on cultural probe projects it’s important to be flexible and think what suits this particular circumstance and not be driven by what’s perceived to be the ‘right’ way of doing things.

And with a lot of usability work, combinations of activities really have a lot to offer, so conducting a cultural probe in conjunction with contextual enquiry, for example, is a great way to go.

Figure 3 – A multimedia cultural probe pack.

S2D: What about when intranets are used in interstate or in rural offices?

GG: Normally, probes are something you’d use to go somewhere you can’t go yourself, to gather information you can’t, where your presence might affect the way people behave, or to gather information over a long period of time.

It would seem to me that in an intranet environment, the gathering of information over a long period of time would be the most likely to be applicable.

But if the organisation is distributed across the country, one of the things you could certainly do is conduct a smallish contextual enquiry then use a cultural probe. Let’s say you want to see four different user groups across multiple states or territories, so you go and see just one representative from each of the four user groups.

That’s just four site visits, and then based on that, you say these are the sorts of things we think we need to explore further, and build a cultural probe activity around that. You can distribute it fairly widely.

Conclusion

As a form of longitudinal user research, or research in situations where you can’t normally go, cultural probes are an excellent choice.

Just as with any form of user research, there is preparation to be done — particularly in selecting participants — and the success of this technique rests on the quality of this preparation.

However in comparison to alternative techniques, cultural probes require less effort for the number of participants you can involve and the richness of the information you receive.

An intranet team looking to get a better understanding of how staff are using the intranet and the issues they face when doing so, should consider cultural probe techniques, especially where other types of user research would be less convenient and cost effective.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Gerry Gaffney for his cooperation on this article.

Photo credits

- Figure 1: Licenced from Photos.com

- Figure 2: Information and Design

- Figure 3: University of Sydneyhttp://praxis.cs.usyd.edu.au/~peterris/images/culturalprobe.jpg